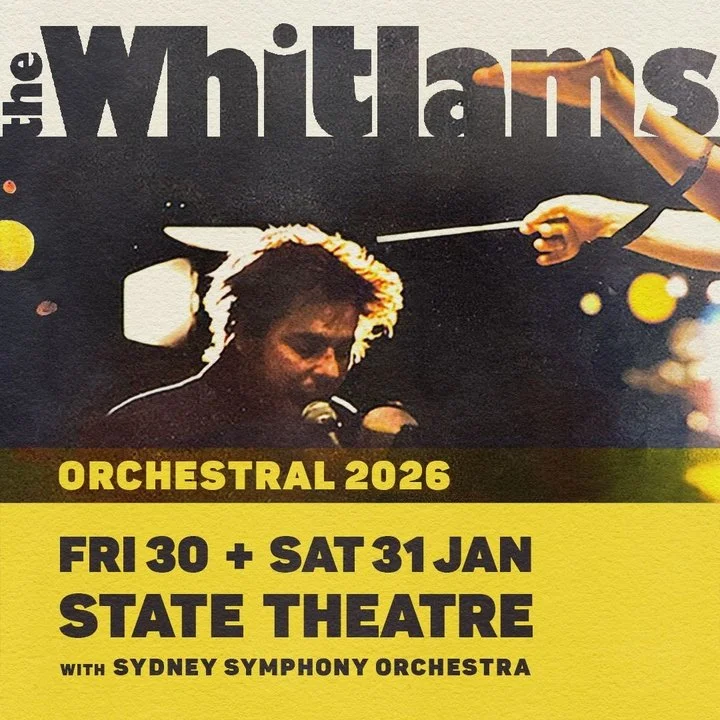

The Whitlams - Orchestral 2026

The State Theatre didn’t host a concert today, it hosted a beautifully controlled riot.

Sydney had that late-January stickiness in the air, the kind that makes the city feel slightly unbuttoned, even in daylight. Out front, people arrived dressed like it mattered but not like they were trying too hard. Inside, the crowd was vibrant and eclectic, a soft buzz of murmuring that kept rising like a kettle almost at boil. Every seat had a curious little flyer waiting, politely asking us to upload footage later, with the promise that the “song to film” would be revealed in the second set. Someone a row behind me whispered, “This feels like homework… but the good kind.”

Before a word was sung, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra did what only a great orchestra can do. They made tuning feel like theatre. House lights dropped. Black-clad musicians took their places with that calm, purposeful rustle of pages and bows and breath. The stage was bathed in a deep blue wash, and above it all hung a scatter of single lightbulbs, like a moody lounge room floating in the dark. The principal violin kept sounding a note, over and over, a lighthouse beam for everyone to lock onto. Nearby, someone murmured with quiet awe about how even this moment felt intentional, like we were already being let in on something special.

Then conductor Nicholas Buc arrived to huge but polite applause, spot lit and back lit like a man stepping into a painting. He didn’t grandstand. He just lifted the room by being there, the quiet authority of someone who can steer a ship through weather.

And then the ship got its singer.

Tim Freedman walked out in a purple suit that looked like it had been cut from pure mischief, flanked by a woman who would soon turn the day into something unexpectedly personal. Beauty in Me opened the show and it landed softly at first, almost tender, until the harmonies arrived and the air changed. The female vocal was beautiful and sure, then she took the lead later in the song and suddenly it was not just a Whitlams moment, it was a family moment. By the last verse, they were singing together, and it felt like the room collectively sat a little closer to the edge of its seat.

Only after the applause did Tim let us in on the twist. Two weeks ago, he said, he’d lost his falsetto in a poker game. That’s why his daughter Alice had joined him for the arrangement. It was funny, of course, because it’s Tim and he can sell a line like nobody else. But it also had that emotionally honest undertone. Sometimes life takes something off you and hands you something better back.

When Midnight Visit began, the rest of the band joined the stage to a proper swell of applause. Guitarist Jack Housden and bassist Matt Fell appeared in dark suits and white shirts, looking sharp against that blue-indigo mood. Tim moved to the grand piano, and the whole stage picture snapped into focus. Out the back, drummer Terepai Richmond sat in a white shirt and trilby, suddenly caught in a spotlight that made him look like he’d wandered in from a smoky jazz club and decided to stay. There was percussion tucked in with him, sharing the rear of the stage like a heartbeat you could feel more than see.

And then the Charlie songs arrived, those strange, funny, bruised little postcards. Charlie No. 1 and Charlie No. 2 rolled out under warmer magenta light, the orchestra shifting colour like it was breathing with the story. Somewhere in there, that “buy now, pay later” lyric floated through, equal parts grin and gut-punch. Tim introduced Keep the Light On as “Charlie two and a half”, and it fitted perfectly. Same world, older eyes. Same ache, a bit more wisdom around the edges.

Then the mood turned, and you could feel everyone lean in.

Tim spoke about his good friend and collaborator Stevie Plunder, thirty years gone now, and dedicated Charlie No. 3 to him. The room got quieter in that particular way a theatre does when it realises it’s being trusted. Tim also pointed out, with typical Whitlams candour, that they’d put Terepai right at the back so he and the conductor could see each other and keep the whole thing “in time… mostly”, which earned the sort of laugh that comes with affection. Not at them. With them.

A little later, Tim gave a nod to arranger Daniel Denholm, who was in the house with his son Elliot for his first ever concert. That got a ripple of applause that felt genuinely protective, like everyone silently agreed to make it a good one for the kid. Then came a story about their tour manager, Greg Weaver, nicknamed Sancho, who’d been with them for more than two decades and had passed away. Tim described Sancho’s advice for when he was off the “singing sauce”. Go on stage with a glass of red wine, because “you don’t want them to think the grog has beaten you. The line got a laugh, but it also told you something about The Whitlams. The humour is real, but it’s often carrying grief in its pocket.

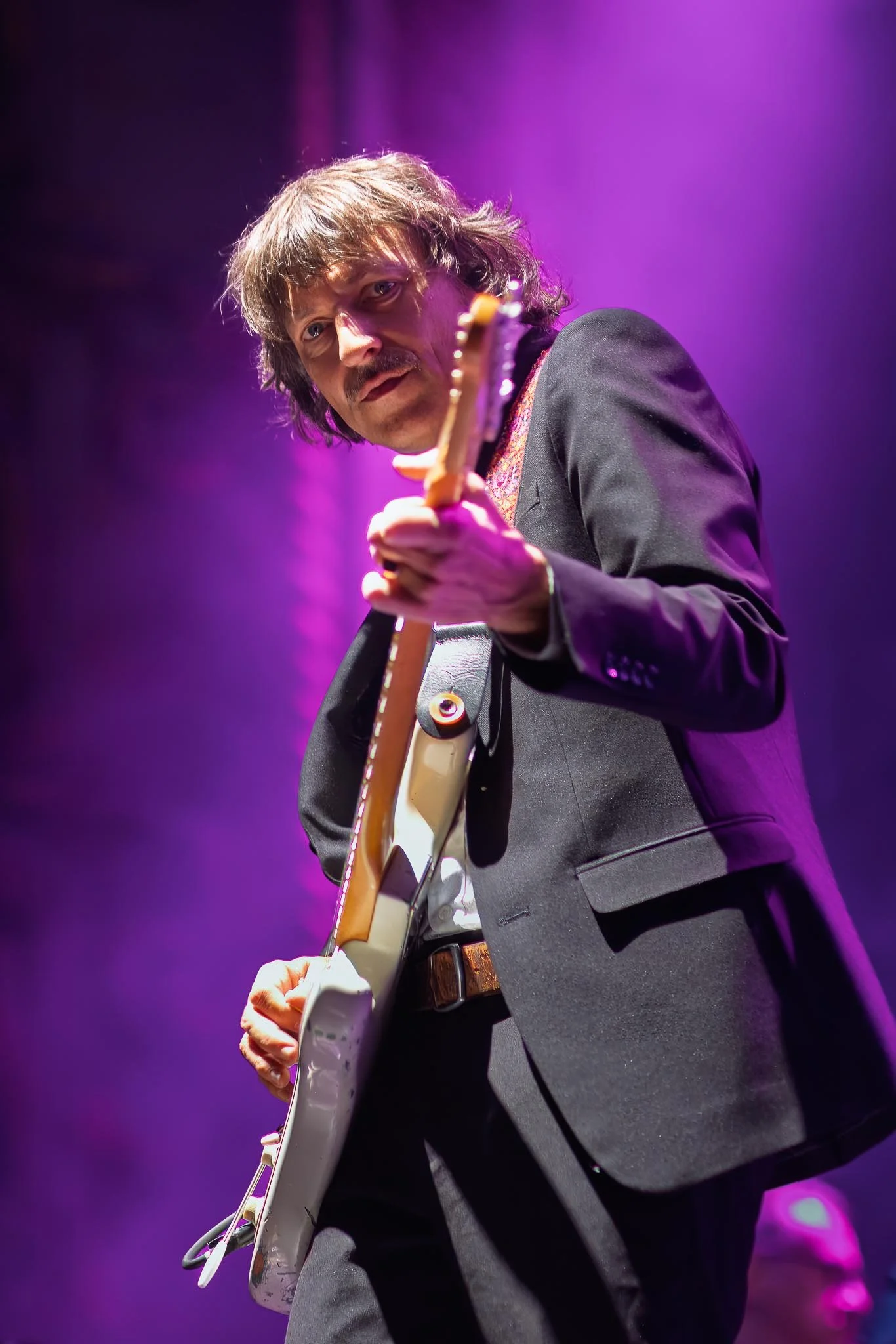

Nobody Knows I Love You followed, and it ended with a Jak Housden guitar solo that didn’t show off so much as it testified. Clean, ringing notes that seemed to find little pockets of air in the theatre and light them up. Fallen Leaves came next, the orchestra now washed in green, and it felt like watching a memory become physical. Strings don’t just support Whitlams songs, they reveal them.

Cries Too Hard arrived under a bright white light that made everything feel more exposed, more honest. At the end, Tim introduced the Sydney Symphony Orchestra properly and conductor Nicholas Buc took his bow, and the applause swelled into something less restrained. Not wild yet, but definitely louder than polite.

Then Tim set up Two Little Boys by talking about a lyric written in the 1890s, and how he put his music to it. What followed made it unmistakably clear how far this version has travelled, elevated and expanded into something richer, deeper, and worlds away from the baggage of past interpretations. Warm white light, voices held carefully, and that strange feeling of time collapsing, old words and new music meeting in the middle.

The first set closed with The Curse Stops Here, stripped right back. Tim at the grand piano, strings close and intimate. No need to reach for anything. It was the kind of quiet that makes you aware of your own breathing, the kind of stillness you only get when a room of strangers is paying attention in exactly the same way.

If the first set was about trust, the second set was about release.

There was a shift in the air as soon as the band returned, like the crowd had decided it was time to stop being well-behaved. The flyer mystery still hovered, but the energy had sharpened, that feeling of “something big is coming”. And when No Aphrodisiac loomed, you could practically hear the anticipation. The applause before it was loud. The applause after it was louder, less “State Theatre matinee” and more “Sydney, you’ve been holding this in for a while”.

Then Tim welcomed Alice back and the whole room got its instructions. Lights up a little. Phones out, if you want. We were going to help create a live recording. Beauty in Me returned in a different arrangement, and suddenly the flyer on the seat made perfect sense. It wasn’t a gimmick. It was a love letter. A father and daughter inviting a theatre full of people to hold something with them and send it back out into the world. A woman near the front smiled at her phone screen and said quietly, “This one’s going straight to the family group chat.”

Later, Tim introduced Year of the Rat with a story about writing it in 2004, when Sydney nightlife felt dire, and then, as if to prove his point, the lockout laws arrived. He joked that the good news is they were removed last week, and that Enmore Road had gotten so crazy he’d had to move out and leave it to the young kids. It was classic Freedman. Half observational comedy, half civic lament, all delivered with that grin that says he’s allowed to say it because he’s earned it.

And then came one of the night’s great cinematic moments. Out the Back expanded into something epic, and the strings didn’t just decorate it, they drove it. Tim spoke about Peter Sculthorpe arranging it, and you could hear the pride in his voice. At one point, Tim left the piano and stood in the wings, holding a glass of red, watching the Sydney Symphony Orchestra with open admiration like he was seeing his own song for the first time. Jak and Matt sat front right, equally in awe. It was beautiful. Not performative, not staged. Just musicians loving other musicians in real time.

Tim told the story of Peter calling him one day and saying, “I’ve finished that string thing.” Peter had proudly declared it was the most he’d sounded like Duke Ellington. Tim went around to Peter’s house in Woollahra and didn’t leave for two and a half days. Then Tim paused, eyes sparkling, and said, “I’ll need to check the statute of limitations, but when I write my memoirs, I’ll explain exactly what I remember happening in those two and a half days.” The theatre roared. It wasn’t just a punchline. It was a reminder that The Whitlams have always survived by turning life, in all its chaos, into story.

Midway through the second set, before the adults had quite worked out they were allowed to let go, a young girl stepped into the aisle, dancing freely while holding her mum’s hand. The room followed her lead.

The momentum kept building. Thank You (For Loving Me at My Worst) was upbeat and vibrant, the kind of song that feels like it’s grinning at you while it tells the truth. Then Tim raised a glass to Gough and Margaret Whitlam, sharing that he’d once been told that between 1972 and 1974, while he was Prime Minister, Gough used to bring Margaret to see shows here and would queue up and buy tickets like everyone else. That detail landed hard, because it’s so oddly humble. The applause that followed wasn’t for politics, it was for the image. A powerful man standing in line to be moved by art. Then Gough arrived, and for a few minutes the theatre felt bigger than itself.

By the time You Sound Like Louis Burdett was introduced as the last song, the room had fully transformed. People twisted and danced their way down toward the front, bodies moving freely in a space usually reserved for stillness and decorum. On stage, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra remained utterly composed, playing with precision and seriousness in their formal black, while the audience jived and whistled and let go below them. That contrast should not have worked. Instead, it was electric. The orchestra smiled out at the crowd in the same way the crowd had been smiling up at them all afternoon, and the whistles and applause were almost deafening. A man near the aisle laughed in disbelief and said, “This is not what this room is built for… and it’s perfect.”

Then came the final release. Tim, in full ringmaster mode, set up Band on Every Corner with a line that felt like he was talking to all of us, not just the room: “Before we release you savage beasts into the nightlife of Sydney, we’d better notify the police and the press. Look at you, what happened to you?” And with that, the theatre became a singalong. Not a tidy one. A real one. The kind where people aren’t trying to sound good, they’re trying to feel better.

When it ended, the standing ovation was immediate. And in one last perfect piece of staging, drummer Terepai Richmond came to the front to take a bow before the conductor and the orchestra. It was a classy reversal, a nod to the engine room, and it said everything about what this collaboration truly is: not rock band plus orchestra, but equals sharing a room, trading power, lifting each other higher.

You walked out of the State Theatre feeling like you’d been inside something rare: a night that started in blue hush and ended in joyful noise, where grief got a seat beside laughter, where a father found a new voice through his daughter, and where an orchestra reminded everyone that precision can still swing.

Keep the light on, Sydney.

Gallery https://musicfestivalsaustralia.com/event-photos/the-whitlams-orchestral-2026

Review and Photos by Andy Kershaw for Music Kingdom Australia